Chip cards represent the ‘new wave’ in prepayment telephone cards and have been used in most countries in the world. The system was patented by a Frenchman, Roland Moreno, and was first introduced, following a field trial, in France in 1986. Roland Moreno’s company, Innovatron, has licensed the technology to a large number of manufacturers in several countries.

Mention should be made in this context of the Innovatron logo which appears (or should appear – occasionally manufacturers forget) on every chip card made under license from Innovatron. This is a stylised ‘i’ with a large square dot over it. It looks a bit like a golf flag and is indeed often referred to as the ‘flag’. It may be of any colour including white against a coloured background or it may even be in a different texture – matt against a glossy background for example. But it should be there. From a collecting point of view it is quite important since it can be in different places on otherwise similar cards or even missing on some. These are seen as varieties by specialists.

Mention should be made in this context of the Innovatron logo which appears (or should appear – occasionally manufacturers forget) on every chip card made under license from Innovatron. This is a stylised ‘i’ with a large square dot over it. It looks a bit like a golf flag and is indeed often referred to as the ‘flag’. It may be of any colour including white against a coloured background or it may even be in a different texture – matt against a glossy background for example. But it should be there. From a collecting point of view it is quite important since it can be in different places on otherwise similar cards or even missing on some. These are seen as varieties by specialists.

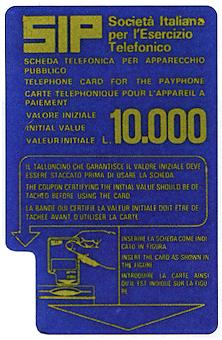

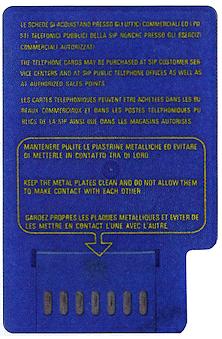

However, the first chip card actually tested was Italian and was made by SGS ATES. Cards of 5000 and 10,000 lira were produced in late 1978, tested in Rome and Turin, and exhibited at Telecom 79 in Geneva. In the best Italian tradition they had removable corners as do the Indian chip cards by Aplab and the Italian magstripe cards.

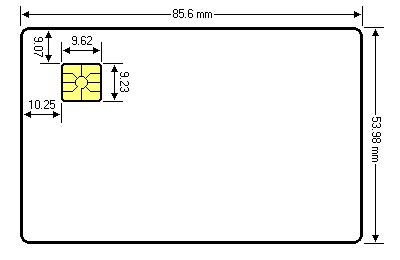

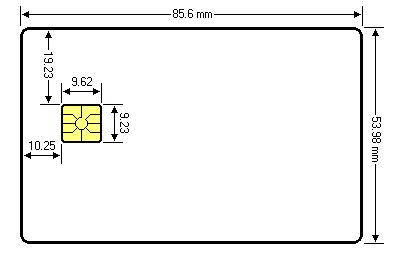

First, however, we should look at these cards more generally and establish the terminology. Establishing the meaning of the words used is especially important because this field seems to generate more misused words than any other apart from politics. A chip card is a card which has embedded in it a microchip, a microcircuit which is generally of silicon although it does not have to be, and which performs the functions required electronically. The size of the chip means that the card has to be at least 0.75mm thick to contain it and is usually a bit thicker than that. The cards are almost always of ISO (International Standards Organisation) ‘credit card size’ although other sized cards have been used. In practice the chip can be in two positions on the card – the French ‘AFNOR’ (Association Francaise NORmalisation) position where the centre of the contact is 14mm from the top edge and 15mm from the left edge of the card and the ‘ISO’ (International Standards Organisation) position which is 24mm from the top edge of the card and 15mm from the left edge. Generally the cards used in France and countries under French influence have had their chips in the AFNOR position while those used in Germany, Spain and the rest of the world have always had the chips in the ISO position. France has later changed over to the ISO position. The French cardphones were adapted to take both types or cards for the change-over period.

The next requirement is for some means of establishing contact between the card reader in the cardphone and the chip within the card. If one examines some of the earlier Schlumberger cards on which the reverse of the chip is sealed with a blob of clear resin, one can see that the actual chip is a block of silicon, about 1mm square by less than that thick, with eight very thin wires coming from it. These wires run to a metal contact on the surface of the card. When the card is inserted into the cardphone, sprung metal contacts within the card reader touch the contact on the card such that the electronic information in the chip can be accessed by the circuits in the card reader. The metal contacts on the cards are usually characteristic and one can see which manufacturer made the card (or at least who made the chip module) from an examination of the contact shape and size. Most of the early contacts were gold plated but some of the more recent contacts have been silver and, even more recently, nickel. The metal used must not corrode easily since this could result in poor contacts within the cardphone and the card would then not work.

Please note that the chip is the small silicon microcircuit embedded within the card and that the gold or silver-coloured metal design on the surface of the card is the contact. There is a tendency, especially in France, to refer to the contact as the chip which is confusing and wrong. It is equally wrong to refer to the normal prepayment telephone cards as ‘smart cards’. A smart card contains a data processor and memory storage which are not needed in this application and which is expensive. The vast majority of current and past telephone chip cards are simply memory cards although some of the multi-application cards, which include payphone applications, introduced in several countries, may use true smart cards eventually. To justify the expense, these could be rechargeable so that they can be used many times.

Similarly it is quite possible to make these cards such that no physical contacts of any sort are required. Inductive or capacitive devices embedded below the surface of the cards allow “contact” with the reader without touching it. Again these “contactless” cards are too expensive for general use at present (perhaps six or seven times the cost of ordinary chip cards) and will only be used where time is very important – they take about 0.1 second to fulfil their function as compared with the half second or more required to insert and withdraw a standard contact chip card. This may not sound like a long time but a queue of people going through a ticket barrier moves some 20% faster with contactless cards so the trend towards multiple applications could again bring the contactless card into use for telephone applications combined with use in, for example, underground transport systems with the higher costs of the cards again being offset by their being rechargeable.

Even the relatively cheap memory-only chip cards used in many countries cost around twice as much as the Landis and Gyr optical cards or the GPT magstripe cards so collectors might wonder where the advantage lies. Apart from chip cards currently being fashionable, there are two perceived advantages – the card-readers are relatively simple and cheap and they also require very little power so that they can operate from the telephone voltage (“line-powered”) and do not require mains electricity to be supplied to the payphones. This can be important in some third world countries and for remote payphones anywhere. It is also claimed that security is higher for chip cards but this is not so certain; at least three cases of successful forgeries of the chip system are known to have arisen in France while I am not aware of either the Landis and Gyr optical system or the GPT magstripe system ever having been successfully broken so far.

There are two basic systems in use. EPROM (Electrically Programmable Read Only Memory) cards are the cheapest and therefore the most widely used. They have about 150 units of memory, only slightly more than a Landis and Gyr optical card and much less than almost any magstripe card. This memory cannot be refreshed so the cards can only be used once. EEPROM (Electronically Erasable Read Only Memory, sometimes referred to as E2) cards have a very large number of units – hundreds of thousands. They are said to be able to be made much more secure but they are about 10% more expensive. A few telcos, such as Venezuela and Korea, have however gone directly to EEPROM cards from the outset.

The tendency in Europe now is towards the “Eurochip” because, apart from compatibility with other European countries leading eventuality to interchangeability of cards as now exists between Germany and the Netherlands, they offer higher security. This is the next stage beyond EPROM and EEPROM. They are EEPROM cards which work on a “challenge and response” basis to check the validity of any card inserted into the reader. The security module within the cardphone can be reprogrammed over the line so that, if it is suspected that security has been compromised, the code can be changed overnight. There can also be more than one code to distinguish whether the card has been used in a payphone or to buy a Mars Bar from an automatic vending machine.

Manufacture is straight forward but, unlike most magstripe and optical cards, they are normally printed individually rather than in sheets. In the early days they were stamped out and the well for the chip module was milled out. The cards were then printed, front and back and, once it was discovered that Scotch tape would remove the design, covered with a protective film. Chip modules (the chips themselves wired to their contacts and set in resin) usually come stuck to a long tape and are then stuck into the cavities prepared for them. The card is then tested, wrapped if required, and boxed. This is still the procedure for higher value cards – for example health or identity cards – but disposable cards are usually injection moulded individually, complete with chip cavities, rather than die cut. Most are of PVC although some are of ABS and polycarbonate has also been used. Some have also been laminated but this is more common for non-disposable cards.